The new firm needs to consider administration and finance issues, too. There are quite a few of each flavor. I list the issues below with my take on what a new firm might consider or the decision that is needed. FINANCE ISSUES Bookkeeping - keep it simple. See our 'Small Firm Accounting' series of articles. Accounting - without other owners in the firm, but with a descent bookkeeping system, you may not need much in the way of accounting to start with. Real accounting is about tax issues, profits and reports about how you are doing financially. You may need this eventually, but not on day one. Debt - to the greatest extent possible avoid debt. Rapid growth is the main need for debt, and even then, you can get in a jam. If you already have a problem, adding debt is really dangerous. Cash-On-Hand - you can't have too much. Shoot for a steadily increasing balance on hand. When you can cover all your expenses for four months, great, that's a worthwhile target. Just keep accumulating more cash. The risks of investing the cash usually outweighs the returns as long as the amounts you are adding are larger than what the investment return would be. Payroll - when you get that first regular employee, get a payroll service to do the payroll. We calculated that it took about 20 hours a month to run payroll and handle payroll taxes, etc. This was using Deltek Advantage software which made it a snap. Doing payroll in house will take about $3,000 a year; a service will cost 1/3 to 1/2 of that. Invoicing - there are lots of ways to do this, even PayPal has an invoicing system that is free. The option of getting paid by credit card is attractive. Whatever you use, use it the first of the month. Don't delay. You already have 30 days of expenses tied up; your client may take another 30 days to pay you; get the invoice in the pipeline for payment right away. Also consider invoicing twice a month. Overhead - you know it is easier to spend money than it is to make money. Act accordingly. Also investigate your options. Every expense that we assumed we needed in 2003 is now available for much less, often 50%+ less than we paid. Rent is the one exception. Setting Hourly Rates - take 120% (adds 20% profit) of your monthly expenses except design consultants; divide that amount by the total number of actual billable hours for the month. That is your AVERAGE hourly rate. Adjust it up and down based on the expertise of the individual. Double check that the chosen rate times the number of billable hours per individual when added together still equals at least 120% of all your expenses. Avoid the impulse to get it exact. It is far more likely that you will have fewer billable hours than that you will have more. There is an upper limit to the number of hours you can be billable, but the lower limit is zero billable hours. The administration issues will follow in the next article. LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THE SERIES

PART 1 - PROJECTS & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PART 2 - MARKETING PART 3 - SALES PART 4 - FINANCIAL MATTERS PART 5 - ADMINISTRATION  So what do you do after the phone rings? Or after your potential client answers your call, or responds to your marketing? There are two things every client is looking for: technical competence and trust. In other words, do you know what you are doing and can I safely put my project in your hands? Once you have your prospect's attention, remember "it is all about them". Let your marketing take care of the competence stuff. If they have concerns, let them bring them up. A competent person doesn't try to convince you of how competent they are. Take the approach of the doctor, but rather than "What seems to be the matter?", start with "What do you have in mind?". Then listen -like a psychiatrist, "I see…"; "What do you mean by that…"; "Tell me more about that…". Let them do 90% of the talking. They don't want to hear what you would do for them until they are sure that you know what they want. From time to time recap what you have been told. Take notes to show you respect their information and want to capture it. If this is a real project, this conversation will go on for an hour or more. If they see you as a commodity, they will ask for a proposal long before an hour is up. Depending on how much you need the work either comply in writing or decline right there on the basis of not knowing enough about their project to prepare a meaningful proposal. Things are not likely to go well for the client that doesn't have time to tell you what he has in mind. When it doesn't, they will remember the guy who 'screwed it up' AND the guy who wanted to do it right. At the end of the meeting promise a recap in writing as quickly as you are comfortable doing it. Don't over-promise and under-deliver. (That's a good rule to live by.) Seeing their thoughts in writing is very powerful. They know they told you this stuff, but this is evidence that you heard them, that 'you get it'. As part of this recap, suggest that you meet again to review what you propose for them. The next meeting is about some first steps that they might want to take. THIS IS NOT A BASIC SERVICES FEE PROPOSAL. Every project has five or six key issues that need to be understood - space needs, desired character, context in which it will occur, legal, political and managerial constraints, a timeline, and a budget. Propose to investigate one or more of these for them. Give them as quick a turnaround as possible (to keep the ball rolling) and a fee that seems reasonable enough that they don't feel like they need to get a second quote to do this 'small study'. This should be in writing and you should outline several first steps, but propose the one that you think will answer a question they want answered. Follow through, and repeat. There are many branching-off directions that this process might take. Improvise. Or better, get some real training from one of the gurus. My recommendation is Stu Rose and Trina Duncan, Professional Development Resources, Inc. They authored The Mandeville Techniques that I have been describing here. They have well-thought-out methodologies for everything - cold calling, proposals, interviews/presentations, everything. Invest in yourself and your career. LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THE SERIES

PART 1 - PROJECTS & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PART 2 - MARKETING PART 3 - SALES PART 4 - FINANCIAL MATTERS PART 5 - ADMINISTRATION  “Marketing is what you do to make the phone ring.” And you have to do a lot of it without much feedback. Marketing tactics are non-client and non-project specific. The marketing activities you should consider include such things as working on developing your niche, building relationships, networking, promotion, RFQs and numerous image or brand-building opportunities. I will touch on each of them starting with the least powerful. However every one of these activities can contribute to what you want your firm to become. IMAGE This is an incomplete list of things that reflect on you and help/hurt your image: firm name, logo, stationery, business cards, physical location, website look and feel, domain-name email, project signs, automobile, clothes, etc. These things don't matter much if your image is a struggling, hungry start-up. However, to the extent that you want to "punch above your weight" and be considered for 'where you are going' rather than 'where you are', they matter a lot. RFQs RFQs take two forms - the private and the public owners. To some extent providing RFQs might be a temporary necessity, but they lead to becoming a commodity. Nevertheless you want to put out information that a private client might find worth considering. The format is up to you. The public clients, like state, federal, and governmental agencies have their qualification processes that vet the firms who want to work for them. At the federal level this is the Standard Form 330. The idea for both types of clients is to put information in front of the people that you think will be selecting architects. PROMOTION Promotion takes several forms such as direct mail, newsletters, ads, sponsorships, events, Facebook(?), and so on. Direct mail consists of sending a letter/post card/brochure/pamphlet or similar piece to a mailing list. Response rates are normally very low, so you are just trying to remind the recipient that you exist. Newsletters could take the direct mail approach or be the email version, which has the benefit of costing about 5% of the hardcopy version. The hitch is that it will take much, much longer to build an email list than a mailing list. Ads are obvious; most are expensive for their return, except the electronic variety using, say, Google AdWords, Facebook or LinkedIn. A sponsorship of someone else's event is like advertising; or you could hold your own event to celebrate a milestone or support a worthy (and related?) charity or civic project. Facebook is a good way to keep your name in front of your "Likes". This could be especially useful if your target audience is individuals rather than organizations. NETWORKING Networking is basically making connections - in person through the Chamber of Commerce, social clubs, alum organizations, church, friends, family; or electronically through LinkedIn, perhaps even Facebook qualifies as networking as long as there is interaction. See Matt Handal's article on how to do it right. RELATIONSHIP-BUILDING Relationship-building is a takeoff on networking; but, at least in my mind, it is different because it is more targeted - you are seeking out people to contact with the sole purpose of finding a way to help them and become their go-to person for all their design and construction questions. NICHE-BUILDING As I have mentioned before, building a niche, while time-consuming (and measured in years), is the ideal form of marketing your firm because eventually you have your clients seeking you out because of your specialty. There is not only less competition, there may be none. Your fees are whatever the market will bear and your productivity is sky high. I would recommend that you do all of these things with the idea of establishing your niche ... say, biophilia-inspired dwellings! LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THE SERIES

PART 1 - PROJECTS & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PART 2 - MARKETING PART 3 - SALES PART 4 - FINANCIAL MATTERS PART 5 - ADMINISTRATION  There is no one time that is better than the next for starting your own firm. There is one key ingredient though. The key ingredient is a paying client with a project. So, as the cliche goes, don't give up your day job … until you have the key ingredient. To a lesser degree you also need to feel competent to do the work you are hired for. Let's cover that first. PROJECT SERVICES You have to feel competent to work on your own or to have colleagues that can assist where you need help. However you can always hire the expertise you need to do the work. Nevertheless you should have a little experience in all facets of designing a project, getting bids, and administering construction. But you wouldn't even be thinking about the possibility of your own firm if you didn't have this issue covered. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT If you can get the clients, you can always find a way to get the work done. The opposite is also true, but with a footnote. It is much easier to hire design help who will produce results than it is to hire business development help who will produce clients. As far as I can tell, this is because the more dependable the business development helper is at corralling work, the more likely he/she will be to start their own firm or find a better-paying opportunity elsewhere. It is more likely, at least at first, that you will need to develop your business yourself. So how will you go about this. Well it helps if you have family connections, but you will find it easier to grow the firm more dependably if you develop a system for getting clients rather than only take advantage of work that is offered to you. So what methods of business development should you consider?

LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THE SERIES

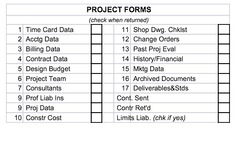

PART 1 - PROJECTS & BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT PART 2 - MARKETING PART 3 - SALES PART 4 - FINANCIAL MATTERS PART 5 - ADMINISTRATION  Every project has some management 'boxes' that need to be checked off besides all the design 'boxes' that you usually focus on. These boxes refer to backstage issues like accounting set-up, working out a design budget, getting a signed contract, and so on. We used to use paper forms to collect the info, and now they are editable PDFs. The whole thing would work better in Basecamp as part of your standard project templates. We will get there. The main problem with this system is that it is often hard to provide the answers when the answers are needed. So things linger in limbo and are forgotten until they affect the project. The perfect example is time-keeping. You can't log time on the project until it has been "set-up". The original form that collected this info was two pages long and asked for a lot of things that couldn't be identified on day one. So we invented a sub-routine for tracking what was still needed. That may have been worse. Eventually we ended up with more forms, each asking for a discreet piece of information when it was needed. In the document below, you can see the forms that we use. You can download a PDF of our PROJECT FORMS here. Use the comments if you have any questions.  Is Twitter useful to architects? Unlike business cards or a logo, which every architect can relate to as a marketing tool, it is not so clear where Twitter fits into an architect's business development toolbox. I think this will provide a little clarity. Let's start with some PROs and CONs for Twitter. PROs

BOTTOM LINE The key to benefitting from Twitter is whether or not you are publishing your own information about your area of expertise. If you aspire to be recognized as a thought-leader in your specialty, Twitter can enhance the perception you want to build. It can also harm the perception you want if your followers don't see a stream of new information coming from you. So whether you use Twitter or not depends on whether you are publishing worthwhile content regularly. For content to be worthwhile it has to tell your audience something they would like to know about a topic that they care about. Even a mundane specialty, say school design, can do this. But a generalist will struggle to find a topic that appeals. A strong specialty, say cancer research labs, should have an easy time demonstrating expertise. Are you interested in writing about your specialty in addition to practicing architecture? The actual writing can be delegated, but you will have to be involved to create the topics and manage the tone. Twitter can assist you in building a reputation, but you will need to do the heavy lifting of building a specialty, which is a very worthwhile endeavor on its own.  What is needed to start an architectural firm today? This is a thought experiment. If you were starting an architectural firm today, how would you do it? At the time of the American Revolution, what did an architect's office look like? Probably not much different than in 1900, except the projects may have gotten bigger. In 1976, what would the differences have been? Well things have changed on the technological front. There are electric lighting, telephones, electric erasers, adding machines, light tables, automobiles for site visits, diazo and mimeograph printing for plans and specifications respectively. There is still that timeless part about needing a client with a project, however. Programming is more sophisticated. But designing and detailing a project isn't really any different. What about today? In 2013 what would be different? What could be different? What should be different? Except for that timeless part - a client with a project - EVERYTHING! You don't need: an office, a phone system, a plotter, a fax machine, a library, flat files, a conference room, a reception area, a server room, a network, a GBC punch and binder, past project files, etc. What DO you need? You may already have some of this. Computer - $1,000 iPad - later ($750) Smart phone - $200 CAD - DesignSight - FREE Basecamp subscription - $25/project for now Invoicing System - PayPal account Bookkeeping service - Wave - FREE Insurance - later ($500) - once you have work Website/Domain/Email - Weebly - $100 Google Apps with Drive - part of Weebly Dropbox - FREE (for additional shared storage) Wide format printer-copier-scanner - $300 Total to get started - less than $2,000 the first year, and about $200/month expenses. You may not need employees for some time. You can farm out work that you need help with to other self-employed architects, who could be anywhere. India? You really can't overstate how much Internet-based services change the need to be in one place with your design team. Add Google Hangout to your repertoire with its ability to share your screen with up to 10 people and you may just be old-fashioned if you think an office is necessary. So, work on getting that client. That is the only real barrier to having your own firm.  Would it work for an architectural team to work from their respective homes or co-work offices? ('Co-work' is the concept where you rent a shared office with other companies -- often for as little as $200/mo.) Or what about working from Starbucks, the local tea shop, the library, a restaurant, your consultant's office, your accountant's office, a co-work sublet, or an office building's shared conference room / equipment. What do you really need? I brainstormed this list of activities that normally take place in the office. I only found four that couldn't be completely addressed by the tools available to you today. For instance wi-fi and LTE devices, Bacecamp, Google Hangouts, Skype, SMS, chat, cloud storage, mobile phones and laptops. Throw Kinko/FedEx or your local repro house into the mix and everything is pretty well covered.

Savings? Looks like at least $1,500 per month -- $18,000 / year

Can't cut loose from having an office? Have a mini-office of one room with two desks and supplies. Or a conference room with scalable tables (ref tables when not a conference table). Go in one day each in rotation. If five people, go in once a week. If seven or eight, go in every week and a half. Etc. - OR - Get an RV and drive it to sites and client meetings. ’Own’ your no-office, nomadic existence. Hold charrettes and bring the ’office’ to them. An intense hands-on experience like a charrette is just made for PR and marketing. Think about it. This economy is going to give you plenty of time to right size yourself for survival. Be creative.  "Style Book - Drafting" For our IntraNet, we have developed several standards that everyone can refer to when needed. We call this our Style Book. Modern software like ArchiCad takes care of a lot of these issues for you. If you are still old-school about drafting tools, meaning AutoCAD and the like, standardize your drafting conventions for the last time. Here are our conventions. Modify to suit your taste. DRAFTING CONVENTIONS - LINE TYPES LEVEL LINES – FLOORS, TOP OF MASONRY, TOP OF CONCRETE, ETC. Show these lines as a light centerline type with a `target' at the end. Place these lines to the left of drawings and details unless clarity is served by placing them to the right. The line usually starts near but not touching the referenced item. Extend all lines away from the referenced item so that the `targets' line up. A `Target' is a circle with cross hairs through its center. The perimeter of the circle is a light line about 3/16" in diameter with the upper left and lower right quadrants filled solid. FINISHED GRADE - Show the Finished Grade as a solid 2.5mm (3/32") thick polyline that represents the desired grade at the face of the wall or other item of construction. Extend the Finished Grade polyline about 8' beyond and in the same plane as the wall, except where other construction intrudes. EXISTING GRADE - Show the Existing Grade as a dashed medium thick line that represents the existing grade at the face of the wall or other item of construction. Extend the Existing Grade line about 8' beyond and in the same plane as the wall, except where other construction intrudes. OTHER LINE TYPES - OVERHEAD LINES - Show lines that occur overhead or behind (not beyond) the picture plane as a dashed line with longer line segments - 1/4" to 3/8" each with 1/16" spacing. Pick a CAD line type that delivers these results. HIDDEN LINES - Show lines which occur below or beyond (not behind) the picture plane as a dashed line with shorter line segments - 3/32" to 3/16" each with 3/32" spacing. Pick a CAD line type that delivers these results. PHANTOM OBJECTS - Show the lines of objects that are missing as a dotted line with dots or extremely short dashes space closely together. Pick a CAD line type that delivers these results. Alternatively use a "GHOST" line weight. DRAFTING CONVENTIONS - LINE WEIGHTS LINE WEIGHTS - Line weights convey information and make a drawing easier to understand. The line weights that we use are as follows - name/color/lineweight/screening/color name: HEAVY / 7 / 0.70 / 100 / WHITE (BLACK) MEDIUM / 6 / 0.50 / 100 / MAGENTA LIGHT / 2 / 0.35 / 100 / YELLOW (GREEN & CYAN, TOO) VERY LIGHT / 9 / 0.25 / 100 / LIGHT GRAY VERY VERY LIGHT / 5 / 0.15 / 100 / BLUE GHOST / 8 / 0.25 / 20 / DARK GRAY LINE WEIGHT USE - PLANS: HEAVY for exterior face of exterior walls; MEDIUM for interior face of exterior walls and for both faces of interior walls; LIGHT for doors, windows, overhead changes of plane (long dash), below floor construction (short dash) and notes; VERY (LIGHT for stair construction, plumbing fixtures, casework; and VERY VERY LIGHT for showing internal material changes like veneers or poche' of wall materials or designations for wall types. LINE WEIGHT USE - ELEVATIONS: HEAVY for outline of building and any major offsets in plane; MEDIUM for minor offsets in plane (overhang, freestanding columns, etc.); LIGHT for doors, windows, gutters, downspouts, other changes in plane, etc.; VERY LIGHT for mullions, change of materials in the same plane; and VERY VERY LIGHT for showing poche' of wall materials, jointing patterns, texture, etc. TEXT CONVENTIONS All text except titles should be the same size, font/style and case. Our standards are: 3/32" high, Roman S, and ALL CAPS. Use Light line weight for notes (cyan, yellow, green or red) Generally place notes to the right of what they refer to so that the leader is at the beginning of the note. Notes are preferable to key notes; however, use a keynote if space is not available to place the note without overlapping any other lines. Overlapping lines are NEVER desirable and rarely acceptable. The font/style name for titles is `Bold'. POCHE’

Apply the appropriate material designations at the latest possible moment to avoid having to change the poche' as new information is added to the drawing. FLOOR PLANS - None for Schematic Design. Apply at the end of Design Development. Remove 80% of poche' at the start of Construction Documents, leaving poche' at corners and wall intersections for clarity. REFLECTED CEILING PLANS - NA for Schematic Design. Apply at the end of Design Development (if any). Update at the end of Construction Documents. ELEVATIONS - None for Schematic Design. Apply at the end of Design Development. Remove 60% of poche' at the start of Construction Documents, leaving poche' at corners and wall intersections for clarity. CROSS SECTIONS - None for Schematic Design. Apply at the end of Design Development. Remove any 'in the way' during Construction Documents. DETAILS - NA for Schematic Design. NA for Design Development. Apply all poche' at the end of Construction Documents, poche' only after all lines, dimensions and notes have been completed. This is a great article compliments of Bob Borson's Life Of An Architect blog.

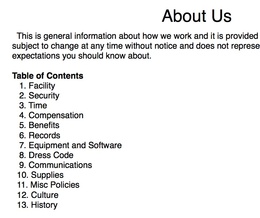

Check it out at http://www.lifeofanarchitect.com/winning-interview-techniques-for-architects/ This should convince you to follow him or subscribe to Life Of An Architect.  "Style Book - About Us" Office Handbooks can be a big waste of time. The bigger they are the less likely they will be consulted. Once you set policy, you are responsible for enforcing it. Bleah! In our office Style Book (IntraNet). we opted for an About Us page containing expectations. See what you think... Download About Us here.  I call them Constraints. You may know them by another name. Obstacles. Restrictions. Hurdles. Red Tape. No matter the project, there are always constraints. There is nothing sexy or exciting about constraints, but you ignore them at your peril. Clients expect you to know about such things. In almost every case, you will have to surrender to constraint's influence eventually, often at great cost for re-working your design to comply. As the world gets more sophisticated and complicated, the list of potential constraints grows. Building code and zoning used to be about the extent of the constraints you might face. Now the list is at least 15 topics. Besides Building code and zoning, we have added storm water management, hazardous materials, department of transportation, ADA (which now applies to everything), special inspections, and a number of issues that are client-driven but not always obvious. Our Constraints Checklist is downloadable here. To address the growing list of client-specific Constraints, we have also developed a questionnaire template to try and elicit this information before it gets to be a headache. Here is the Questionnaire for download too.  Those pesky building codes! Not many things can wreck your building floor plans like code requirements that sneak up on you. Overlooking a seemingly innocuous requirement can set you back hours in the beginning of design and days at the end of design. The only solution is to review the code early and often. This doesn’t have to be as overwhelming as it sounds. Use a checklist at the earliest opportunity to document the requirements that will apply to your project and how your design complies. At the end of the design phase, read over the checklist and update any changes that have occurred, making sure that you are still in compliance. The designer needs to be the one who checks the code, even though most designers hate this. It is the only way to avoid constant re-designs to correct code problems uncovered by your in-house expert (after too much time has been spent doing it wrong). There are a few checklists out there on the Internet that you could use. Those rarely seem that useful. You could create your own. If your work is repetitive, this will save time. Even if your work is not repetitive, customizing the checklist to your needs will save time in the long run. The checklist below is for the International Building Code. It covers the issues that we usually need to check; your need is probably different! Use this one as a guide to make your own.  If you are always presenting ideas - to clients, bosses, team members - here is a new tool for your arsenal, an iPad App called Vittle developed by Qrayon. Vittle has real possibilities for $9. “Turn your iPad into a recordable whiteboard.” “Write a video as easily as an email.” This YouTube video will give you a glimpse of the possibilities. From Qrayon’s website, here is another short video of ideas for use in the workplace. You can download the free version from the App Store to try it out. And finally, their brief Users Guide gives you an idea of the tools at your disposal. You can copy/paste work from their note-taking app that I reviewed earlier this week, InkFlow Plus.  One of the things that I notice about a room is the ceiling. Especially the way a ceiling grid is placed relative to the walls. I think that when the grid terminates against the wall with a tiny piece of tile it looks like shit. I wonder, "Did the architect cause that because of some other relationship that I can't see? Did the contractor just do it?" My mentor taught me better. "No pieces less than a half tile - anywhere." I found that you can almost always do that. It might mean that you have to center the grid intersection in the room, or center a tile in the room, or start with a slightly offset grid. But there is always a solution. If you try. There are special challenges - non-parallel walls, skewed walls, floating items like a section of wall or columns. CAD really simplifies things since you can move a grid around until you are happy with the edge conditions. Include fixtures in that exercise and kill two birds with one stone. Some times there might not be a great solution unless you can change the layout, which seems a bit excessive. Light fixtures complicate things. Occasionally you find that you can't place fixtures where you want and locate the grid ideally. One way to minimize the issues is to use a planning grid of 2'x2' or 4'x4' when laying out the walls in the first place. If you stay on the grid, which is hard to do, you get a great ceiling tile layout automatically. At some point we decided to write a recipe and move on to worrying about bigger issues. We called that recipe: Rules of Ceiling Grid Placement

Rules 2 and 6 are key. Rules 1 and 7 can be violated for good cause. Rules 3, 4, and 5 can almost always be met. I don't like the focus that LEED places on 'social engineering’ issues. Does having a bike rack (1 pt) really help the environment? And how is it that a LEED certified building does not mean that it out-performs an average building? Many don’t. Humans are driven by economics. The focus should be on that. "How do you get a building that is cheaper to operate?" Everybody gets that. Everybody wants that. Except for the strip mall owner who isn't paying the utility bill. I predict that USGBC will marginalize themselves with their ’feel good’ political correctness. The sheer complexity of sustainability keeps most people in the dark about how it all works. For instance, super-insulating a large office building is not helping. Large office buildings are air-conditioned whenever they are occupied because the people, lights and fresh air requirements dwarf the heat loss and the heat gain through the skin of the building. Instead of getting a ’star’ on your LEED ’homework’, which means you may have met some level of trying to be a good person, why not use a checklist that says if you do these things you get these benefits? And leaving energy issues in the hands of the building designers is a bad idea. The people occupying the building have a major impact on energy use - light levels, coffee brewing/warming, space heaters, computers, etc. Before LEED was a thing, there were lists like the No-Brainer list here. You didn't get a star but you got guidance that was useful - to everyone.  Cool Roofs Although the primary concern with roofs is water-tightness, you can also gain benefits for energy efficiency. Roofs make up a large proportion of the heat retaining surfaces in populated areas. In some highly concentrated areas, as much as 27 percent of the land cover is roof surface. This can cause what is referred to as an "urban heat island" - a region where the temperatures can be several degrees warmer than the surrounding area. Buildings with dark roof surfaces get hotter and stay hotter longer. Air conditioners must work harder and longer to maintain comfort for occupants. A reflective or white roofing system can keep a building cooler and save money on air conditioning costs. The ENERGYSTAR® Roof Products Program provides guidance in selecting roofing products, as well as a list of products that meet the qualifications established for cool roofing products. This list of qualifying products identifies low-slope roof products that have an initial reflectance of at least 65 percent and a reflectance of at least 50 percent after three years of weathering. You can explore the ENERGYSTAR® site through this link.  Do You Really Need A New Roof? Years ago I saw a 25 year old tar and gravel roof that you could almost see through it was so worn, but it was only leaking at the edges where the metal gravel stop was embedded in the felts. The movement of the metal had created cracks. Currently I know of a 28 year old roof that is virtually problem-free because it gets yearly maintenance. Replacement will cost $100,000 eventually, but less than $1,000 a year in maintenance has kept that expenditure at bay for over a decade. What should you check before you spend $$$ for re- roofing? • Get more than one opinion. Second and third opinions are necessary. Get advice from the most knowledgeable expert you can find. When all else fails, use a leak detection service (infrared sensing). • Maintain your roof every Fall. Water rarely enters the building through the open surface of the roof - almost always at the penetrations and edges. Yearly maintenance can get you significant extra life. Fall is the best time for maintenance. • Be wary of rooftop equipment. Finally, rooftop equipment is the bane of roofs. A bit of detective work can tell you if any equipment on the roof is near the area of the leak. Many times contractors make "modifications" to your roof with limited knowledge of roofing. Occasionally, their equipment is the source of the leak! If a replacement is truly called for, consider the best roof system that you can afford. The simple fact is that a cheap system will probably be replaced three times before a top quality roof is replaced. The total cost and inconvenience of an inexpensive roof will lose out in a life cycle cost analysis.

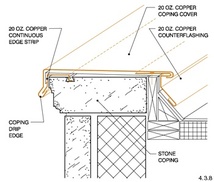

How To Avoid Re-Roofing Our study of "Top Building-related Issues" lists leaking roofs among the top three issues, and often it is number one. You get the impression that you can't beat Mother Nature. Actually, effective roofing projects are completed all the time, but you definitely have to work with nature to achieve success. The average life for a commercial roof is seven years. This is less than half the common expectation of 20 years. The frightening fact: if the average is seven years, half the people are getting even less. One scenario that I suspect is a major contributor to the low life-expectancy of commercial roofs is replacing your whole roof because of a leak that your roofer can't find. The situation is like Rubik's Cube - there are a lot of strategies that don't work. My experience is that there are also many strategies that do work. You should know about these successful strategies. How To Get A Good Roofing Job To help ensure a high quality, trouble-free roof or re-roof project, which may not end up costing you any more, add the following requirements to your bidding documents and insist on their implementation: • Unconditional 2-year workmanship and water-tightness warranty. (Kentucky Department of Education requirement) • Manufacturer's standard warranty of 10, 15 or 20 years - the longer the better. • A Contractor's Qualification Statement with slightly higher than typical requirements for years in business and number of similar roof projects, say, 10 years and 20 projects. • Clear and specific details of every joint, termination, change in materials, and flashing condition. • Pre-installation meeting with attendance required for manufacturers' representatives from both the insulation and roof membrane companies. • A schedule with a representative from the roof and insulation manufacturer present on each day when their product is being installed and flashed. The norm is one visit at the end of the job when things are hidden from view. That is not adequate.  Roof Flashing The roof is one of the most essential parts of a building as it protects occupants, contents and interior of the structure from the elements. The most pervasive and difficult weather element to control is water. Roof flashing is usually the last line of defense in the battle against water penetration. Flashing forms the intersections and terminations of roofing systems and surfaces to thwart water penetration. Locations include: wall flashing, expansion joints, counter flashing, base flashing, built in valleys, scuppers, gutters, downspouts, exposed trim and fascias. Flashing materials must be durable, low in maintenance, weather resistant, able to accommodate movement and compatible with adjacent materials. Experienced and skilled installers are necessary to plan, cut, shape, fabricate and install complicated shapes into permanent 3-dimensional, continuous forms. Copper flashing offers beauty in its familiar protective green patina and a long-service life; it will not need to be replaced when the roof is replaced. On a life cycle cost basis, copper flashing is the best choice. A close second is stainless steel. Copper isn't appropriate for every project.  PART THREE - WORKING WITH CONSULTANTS ’If they’re not calling, then they're not working on it.’ That is the first thing to remember. Don't wait for them to call. Make sure they know you expect them to meet the schedule. When you set up the schedule, consider intermediate checkpoints to review progress and facilitate coordination. Here is what we usually do for the design phases, along with some expectations of their phase deliverables. The percent complete refers to the architect's progress. Schematic Design: 75% review - final review. During SD you will need to get out ahead of the consultants. The main thing you need from the consultants during SDs is feedback on adequacy of utilities, their location, systems they foresee, likely ceiling space needed for those systems and budget expectations. Design Development: 40% review - 80% review - final review. During DDs you will need the consultants to start layouts, work out equipment locations, especially those that require space. They need to refine their thinking about the systems that will be used. By the end of the phase, the mechanical and electrical equipment locations should be nailed down with confidence. Main duct sizes and routes should be known. and verified that they fit. Get outline specs or at least cut sheets on the fixtures and fittings that are proposed. Construction Documents: 30% review - 60% review - 90% review - final review. During CDs everything needs to come together for a final solution. For smaller jobs, you might change the reviews to 50-75-95-final because the consultants will find it hard to not just run with it. The review meetings serve two purposes - a chance to get everything discussed and coordinated, and a chance to make sure the consultants will meet the schedule. Particularly during CDs, these review meetings should involve the whole design team. The M/E or the Architect could host the meetings. Invite consulting disciplines to attend on a schedule that allows 30-45 minutes to discuss that discipline. The Architect and M/E project managers would attend all sessions. If the project has a Construction Manager, he would attend the whole meeting as well. For the Bidding phase the only requirement for the consultants is to prepare their items for any addendum. For Construction Administration the minimum that you will need from the consultants is to review the submittals for their discipline and to make two or three site visits with reports. How much more you wish them to do is variable. Some options are: attend progress meetings, more site visits, respond to Requests For Information, review percent complete of their discipline's work for the pay request review. You can find the other Parts of this series here:

Part 1 - Background http://www.architekwiki.com/1/post/2013/04/guidelines-for-working-with-consultants-background.html Part 2 - Hiring http://www.architekwiki.com/1/post/2013/05/guidelines-for-working-with-consultants-hiring.html  PART TWO - HIRING A CONSULTANT When you are sizing up a consulting firm here are few suggested TO-DOs ___ Visit their office. Do you like what you see? ___ What is their head count? Does it seem like a good fit with your firm? ___ Ask how they are organized. Do you like what you hear? ___ What role does the 'mother ship' play if the firm is a branch office? ___ Ask, "What do you do about quality control?" If they have a QC team, that is a good sign. ___ Ask how much contingency you should include for change orders. More than 2% could be a problem. The M/E consultant's attitude to change orders is a good gage of how well their Quality Control works. ___ Do they carry professional liability insurance? ___ How will they schedule their work for you? Does it seem well-thought-out? ___ What is their procedure for estimating? Do they recommend a contingency to cover their accuracy? ___ Ask who you will work with. Assigning your project a project manager is a telling issue. If you will work with each discipline directly, my experience is that they don't communicate internally and you are expected to coordinate their work for them. Depending on your level of experience and available time, this can work; but good firms use a project manager. When you find a firm that you are happy with and want to work with, the next step is to work out a fee and scope of work for the project under consideration. If the fee is higher than you would like, consider negotiating the scope of work they will provide to get the fee in line with your plans. You can find the other Parts of this series here:

Part 1 - Background http://www.architekwiki.com/1/post/2013/04/guidelines-for-working-with-consultants-background.html Part 3 - Working http://www.architekwiki.com/1/post/2013/05/guidelines-for-working-with-consultants-working.html |

x

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

Architekwiki | Architect's Resource | Greater Cincinnati

© 2012-2022 Architekwiki

© 2012-2022 Architekwiki